Dispelling Myths about the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative

- Issue brief, Journal article

Rebecca Mannel, MPH, IBCLC

Clinical Associate Professor and Director of the Oklahoma Breastfeeding Resource Center (OBRC)

Jaclyn Huxford, RDN/LD, IBCLC

Assistant Program Director, Technical Operations at the Oklahoma Breastfeeding Resource Center (OBRC)

Sara McManus, MS

Financial and Administrative Manager at the Oklahoma Breastfeeding Resource Center (OBRC)

Haley Richardson, BS

Education Program Coordinator at the Oklahoma Breastfeeding Resource Center (OBRC)

Abstract

The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) is a global program designed to recognize hospitals that ensure mothers and infants receive timely and appropriate care that support optimal infant feeding and mother/baby bonding during the birth hospitalization. It was developed by the World Health Organization and UNICEF in 1991 and has been shown to increase breastfeeding initiation, duration and exclusivity rates. Despite its proven benefits, misconceptions about BFHI can deter hospitals from participating.

The Oklahoma Breastfeeding Resource Center (OBRC) works to improve the health outcomes of mothers and babies in Oklahoma by providing the needed support, guidance, and infrastructure that hospitals need to implement Baby-Friendly practices and achieve BFHI designation.

This issue brief will address misconceptions about BFHI and provide evidence supporting its powerful impact, including reducing racial and ethnic disparities in breastfeeding, increasing breastfeeding initiation and continuation rates and empowering families.

Description of the problem

Breastfeeding is a known health prevention strategy with multiple lifelong impacts on both mother and child. The recommended breastfeeding duration is six months exclusive breastfeeding or breast milk feeding and continued breastfeeding for two years and beyond.1Meek et al., 2022. Breastfeeding duration is significantly impacted by the care that is provided during the birth hospitalization. Results from a nationwide Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) study demonstrated a 13-fold increase in premature cessation of breastfeeding within the first six weeks postpartum when suboptimal breastfeeding care was provided in the delivery hospital.2Digirolamo, et al., 2008. Evidence-based guidance exists for hospitals providing maternal/newborn care in the form of the internationally recognized Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI).3World Health Organization, 2018.The BFHI has been shown to improve breastfeeding outcomes, reduce disparities in breastfeeding and ultimately reduce healthcare costs through increased breastfeeding duration rates.4Bartick et al., 2013; Digirolamo et al., 2008; Merewood et al., 2019; Hudson et al., 2020.

Nationally, 25.7% of babies are born in Baby-Friendly designated hospitals while 30.6% of Oklahoma hospital births occur in Baby-Friendly hospitals, above the national average.5Baby-Friendly USA, 2024; OBRC, 2024. The Oklahoma Breastfeeding Resource Center (OBRC) partners with the Oklahoma State Department of Health (OSDH) to support Oklahoma hospitals in achieving Baby-Friendly designation. The state project known as Becoming Baby-Friendly in Oklahoma (BBFOK) has been supported through an OSDH contract utilizing federal funds from a Maternal and Child Health Services Title V block grant since 2012. The BBFOK project has led to 12 hospitals achieving Baby-Friendly designation, 10 of which have continued getting re-designated every five years.6OBRC, 2024. In 2024, OBRC received a Discovery grant from the Tobacco Settlement Endowment Trust (TSET) with the objective of supporting an additional ten rural Oklahoma hospitals to achieve Baby-Friendly designation and improve breastfeeding outcomes in rural counties, recognizing the impact that BFHI designation can have on breastfeeding duration and exclusivity. This new project is known as OBRC’s Advancing Infant and Maternal Health Initiative (AIM-HI) and is currently recruiting rural birthing hospitals to participate and receive as much as $35,000 in financial support over three years.

Research/data overview

Infants in higher income countries who are not breastfed are at increased risk of obesity, diabetes, otitis media, gastroenteritis, atopic dermatitis, asthma and life-threatening illnesses such as lower respiratory infections, leukemia, necrotizing enterocolitis and sudden infant death syndrome.7American Academy of Family Physicians, 2022; Meek et al., 2022. Children who were not breastfed also have higher mean blood pressure and lower intelligence test scores. A 2017 publication estimated that over 45,000 cases of childhood obesity could be prevented annually with optimal breastfeeding while a 2021 CDC study reported that breastfeeding initiation alone was associated with a 27% reduction in odds of post-perinatal infant mortality across multiple racial and ethnic groups.8Bartick et al., 2017; Li et al., 2021. Women who do not breastfeed have increased risk of diabetes, postpartum depression, breast, ovarian, endometrial and thyroid cancers, hypertension and cardiovascular disease.9Meek et al., 2022; Bartick et al., 2013. Longer duration of breastfeeding/lactation for the mother can increase weight loss after pregnancy and help sustain that weight loss, contributing to lower risks of obesity in women.10AAFP, 2022; Meek et al., 2022.

Breastfeeding rates in Oklahoma, while improving in recent years, still lag behind national averages with 78% initiation vs 84.1% nationally and a rate of exclusive breastfeeding at six months of 20% vs 27.2% U.S.11CDC, 2024. Oklahoma ranks 47th and 48th respectively for those two outcomes. Compared to urban areas, rural counties in Oklahoma have significantly lower breastfeeding initiation rates, with several below 70%.12CDC, 2021. As noted above, obesity and diabetes for both mother and child are significantly reduced with longer durations of breastfeeding. Obesity rates in Oklahoma are well above the national average. The CDC reports 40% of Oklahoma adults as obese with a ranking of 49th and another 32% of adults as overweight.13CDC, 2022. For children enrolled in the Women, Infants and Children Supplemental Nutrition Service (WIC), 13% of 2–4-year-olds are obese and 15% are overweight.14CDC, 2020. Adult obesity rates increase in rural counties with 43 Oklahoma rural counties having obesity rates over 40% and 9 of those over 50%.15OSDH, 2023. In addition, Oklahoma has one of the highest rates of diabetes prevalence at 13.3% of adults.16OSDH, 2024.

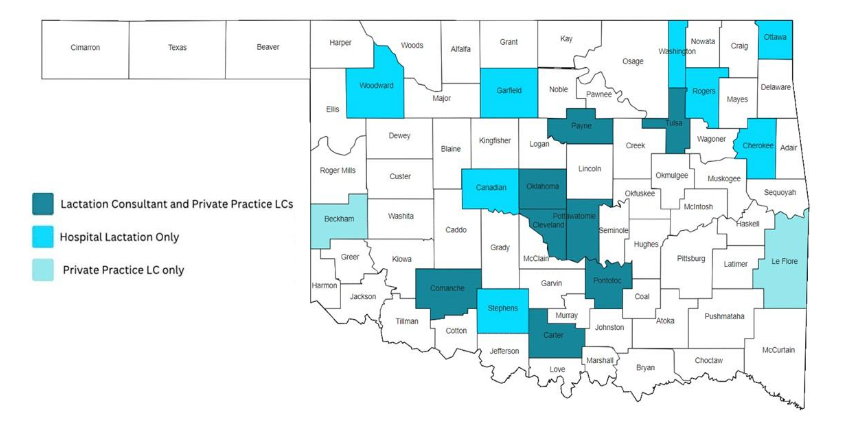

There are 24 birthing hospitals in rural Oklahoma counties, six of which are designated Baby-Friendly, leaving numerous areas throughout Oklahoma without the vital best practices of optimal infant feeding care. These lactation care deserts are communities with minimal to nonexistent resources and support mechanisms for breastfeeding and lactation care. Of Oklahoma’s 77 counties, 59 are lactation care deserts meaning a county with no Baby-Friendly hospital and no International Board Certified Lactation Consultants (IBCLC) available for clinical lactation care either in the hospital or in the community. See Figure 1. To further exacerbate this access to care issue, the March of Dimes cites almost 52% of Oklahoma counties as maternity care deserts, the third highest in the U.S., where there are no delivering hospitals nor any obstetric providers.17March of Dimes, 2024.

2024 Oklahoma Lactation Care Deserts

Figure 1: 2024 Oklahoma Lactation Care Deserts (Oklahoma Breastfeeding Resource Center), Oklahoma Lactation Consultant Resource Guide, 2023.

An IRB-approved survey developed by the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center was distributed to all OSDH/WIC clinics, independent WIC clinics and three tribal WIC clinics for a total of 10,000 surveys. Over 5,000 surveys from English and Spanish-speaking mothers were completed for an approximate 50% response rate. Only 53% of mothers reported that their baby was breastfed or fed human milk for their first feeding and only 31% were advised to give only breastmilk (i.e., exclusively breastfeed). While 59% were shown how to breastfeed, almost half (49%) were offered formula. Only 43% were given a telephone number to call for help, despite the existence of the toll-free, 24/7 Oklahoma Breastfeeding Hotline. Less than 4% were offered donor human milk if baby needed a supplemental feeding while 53% were given formula. Baby-Friendly hospitals must demonstrate that 80% of the time mothers were advised to exclusively breastfeed, shown how to breastfeed, given a telephone number to call for help and offered formula when maternal milk or donor human milk are not available.18Baby-Friendly USA, 2021.

When hospitals achieve Baby-Friendly designation, not only are breastfeeding initiation and exclusivity rates increased, the racial and ethnic disparities in breastfeeding are significantly reduced. A CDC funded initiative focused on southern U.S. states that historically have lower breastfeeding rates. After achieving BFHI designation or being very close to designation, the breastfeeding disparity gap between Black infants and White infants decreased by almost 10%.19Merewood et al., 2019. Although breastfeeding outcomes increased across all races and ethnicities, these increases were particularly pronounced for Black families. Amongst those Black families, breastfeeding initiation increased from 46% to 63% while rooming-in was associated with a significant increase in exclusive breastfeeding at discharge, from 19% to 31%. In a 2022 CDC survey, only 48% of Oklahoma birthing hospitals self-reported that “few breastfeeding newborns receive infant formula” indicating that most breastfeeding babies are not exclusively breastfeeding when discharged from the hospital.20CDC, 2023.

Key takeaways

If the BFHI can have such a powerful positive impact on breastfeeding rates, why are so few hospitals putting this program into practice? Implementing a rigorous quality improvement project such as the BFHI is challenging for most hospitals and particularly challenging for rural hospitals that typically have fewer resources than urban hospitals. Families delivering babies in lactation care deserts also have fewer community resources, both prenatally and after hospital discharge, two key steps that are part of the BFHI process. Of the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding, the foundation of evidence-based BFHI practices, Step 3 requires prenatal breastfeeding education for all families and Step 10 requires connecting families to skilled breastfeeding support in the community after discharge. These two steps are often cited as the most difficult for hospitals to complete.21Munn et al., 2016. While significant funding is available through the AIM-HI program to offset most of the costs of implementing Baby-Friendly practices and provide technical assistance to overcome barriers, misconceptions about the BFHI can deter birthing hospitals from participating.22Baby-Friendly USA, 2024.

Some common myths include:

Myth: Baby-Friendly hospitals require mothers to breastfeed, thus taking away their “choice.”

Fact: The BFHI promotes informed decision-making by families, so it does require that prenatal education about the importance and management of breastfeeding is provided to all expecting parents. Mothers do not have a choice about how to feed their babies if they know nothing about breastfeeding, have never known or seen anyone breastfeeding a baby and their only exposure to infant feeding is bottle-feeding formula. Not all mothers will choose to breastfeed, some are not able to, and some babies will require formula-feeding or supplementation due to medical reasons. “Baby-Friendly designated hospitals are expected to treat all mothers with dignity and respect regardless of their infant feeding decision.”23Baby-Friendly USA, 2024.[/mfm] With informed choice, more mothers will initiate breastfeeding and, if they deliver in a Baby-Friendly hospital, more babies will leave the hospital exclusively breastfeeding.

- Myth: Baby-Friendly hospitals cannot use any formula so mothers who choose to formula feed must bring their own.

Fact: Baby-Friendly hospitals cannot accept free marketing gifts from the formula industry, including free formula for newborns, or free formula marketing gift bags to send home with new parents. Hospitals must pay fair market value for any formula products they use. This policy is consistent with all other areas of the hospital where the hospital pays for any food or medical nutrition provided to patients. New parents deserve access to evidence-based information and an environment free of commercial interests. While Baby-Friendly hospitals support and respect a mother’s infant feeding decision, in a Baby-Friendly environment, more mothers will choose to breastfeed and succeed at breastfeeding thus reducing the need for infant formula products. Parents who choose to formula feed will be provided with formula to feed their babies and education on safe formula preparation, feeding, and storage as well as access to formula feeding resources after discharge.23Baby-Friendly USA, 2021. Myth: Baby-Friendly hospitals cannot have a well-baby nursery so mothers must have their baby in the room with them 24/7 regardless of the mother’s fatigue or lack of sleep.

Fact: There is no requirement for closing the hospital’s nursery in Baby-Friendly guidelines. Rooming-in at least 23 of 24 hours each day should be the standard of care unless there is a reason it is not possible (e.g., medical or safety) or by informed decision-making on the part of the parent. When parents know that their baby will stay in the room, they are more likely to arrange to have a support person who can stay overnight to help. In cases where a support person is not available, hospital staff will work with the mother to help her get needed rest. Some hospitals discover that their nursery is no longer being utilized due to their success with rooming-in and its popularity with parents. Hospital leadership may then decide to make better use of unused space but that is a hospital decision, not a Baby-Friendly requirement. Most parents are empowered to know that their baby will not leave their care unless there is a medical or safety reason.24Hakala et al., 2018.

Myth: Skin-to-skin care can lead to unsafe sleep practices and an increased risk of a sleep-deprived parent dropping their baby.

Fact: Skin-to-skin care supports important physiological processes for the baby, such as stabilizing a newborn’s heart rate, temperature, and blood sugar. The increased oxytocin response in both mother and newborn helps them to relax, stimulates milk release for the mother and bonding for both. Sleepiness is a normal part of this process, so parents and staff need to understand how to practice safe skin-to-skin care while staff continue monitoring the baby. In the hospital, parents can ask for help from staff in putting their baby on his or her back to sleep in a safe location, typically the hospital bassinette. Once at home, parents need to identify a safe sleep location for the baby that is close to the parent’s bed.

Myth: Baby-Friendly hospitals must meet a target rate for exclusive breastfeeding (EBF), or they lose their designation so hospital staff will not bring formula if a mother requests it.

Fact: There is no minimum EBF rate that hospitals must attain though they are expected to monitor and report EBF rates. If a hospital is not seeing any increase in EBF rates, then leadership should explore why and determine if any quality improvement measures are needed. Maternal request for formula is very common so bedside staff are expected to explore why the parent thinks formula is needed, provide appropriate education to support successful breastfeeding and honor the request for formula if the parent still desires.

Policy implications

Both the public and the healthcare community (providers, hospital leadership, staff) benefit from education about what a Baby-Friendly hospital is and what it is not. After overcoming the common misconceptions and other barriers and ultimately achieving Baby-Friendly designation, sustainability is the final key. Once designated, hospitals must maintain their designation through continuous quality improvement, annual fees and onsite assessments every five years. OBRC’s OSDH funding covers a portion of Baby-Friendly fees (as funding is available) while the TSET grant is limited to three years of support. At least two previously designated Oklahoma Baby-Friendly hospitals have discontinued their designation, and cost is certainly a factor. Prior to the Oklahoma Health Care Authority’s transition from a fee-for-service Medicaid system to the current managed care system, Senate Bill 183 was introduced to incentivize Baby-Friendly designation through slightly higher reimbursements to hospitals for obstetrical care. This bill had support from a number of hospitals yet did not advance as the Medicaid transition was starting. Now that there are three managed care organizations, it is time to explore a new way to achieve the same goal.

One model exists that was launched in 2021 by Blue Cross and Blue Shield (BC/BS) of Mississippi. To achieve the BC/BS Blue Distinction designation for maternity care, all network hospitals must achieve Baby-Friendly designation. The BC/BS Maternity Care Quality Model “encourages and reinforces best-practice guidelines and patient-centered care,” which is exactly what the BFHI epitomizes. In 2015, Mississippi had only one Baby-Friendly hospital. As of September 2024, 31 out of Mississippi’s 42 birthing hospitals are designated Baby-Friendly.25CHEER Equity, 2024. Of those 31, nine have been re-designated, two are pending and the remaining 20 are all in their first five-year designation period.26Baby-Friendly USA, 2024. Babies born in these hospitals represent over 80% of the births in the state as compared to Oklahoma’s rate of just over 30%.27Carothers, personal communication, September 27, 2024.

The bulk of the hospitals (28) achieving initial Baby-Friendly designation were supported by the Mississippi CHAMPS initiative. This initiative, Mississippi Communities and Hospitals Advancing Maternity Practices (CHAMPS) was launched in 2014 with funding from two philanthropic foundations. At the end of this initiative, breastfeeding initiation and exclusivity rates significantly increased while the breastfeeding disparity gap between Black and White couplets decreased by 17% (Burnham, et al, 2022). Mississippi’s EBF rates at three and six months, based on babies born in 2021, have surpassed those of Oklahoma for the first time in 17 years, since the CDC began reporting on babies born in 2004. Even more notable is the fact that 11 of Mississippi’s Baby-Friendly hospitals are re-designated or pending, 10 of which did so after the BC/BS Blue Distinction added Baby-Friendly designation to its criteria, the only financial incentive remaining after CHAMPS ended.

Given the fact that almost 60% of Oklahoma births are covered by Medicaid, the Oklahoma Health Care Authority and state policymakers can learn from the Mississippi example in how to incentivize Oklahoma birthing hospitals to not only earn but maintain designation as a Baby-Friendly hospital. Although many factors contribute to our state’s low breastfeeding duration and exclusivity rates, babies born in Baby-Friendly hospitals and their mothers, especially those in lower income brackets, have a higher chance of leaving the birthing hospital successfully breastfeeding. Increasing our breastfeeding duration rates will reduce our tragically high infant and maternal mortality rates and improve the health of Oklahomans for generations to come.

About the author

Rebeccca Mannel, MPH, IBCLC

Clinical Associate Professor and Director of the Oklahoma Breastfeeding Resource Center (OBRC)

Becky has over 30 years’ experience in lactation. She developed the lactation service at OU Children’s which she managed for 15 years. Becky oversees several statewide breastfeeding initiatives, has published numerous peer-reviewed publications and book chapters, edited several lactation textbooks and served as President of three international lactation-related organizations.

Jaclyn Huxford, RDN/LD, IBCLC

Assistant Program Director, Technical Operations at the Oklahoma Breastfeeding Resource Center (OBRC)

Jaclyn earned her Bachelor of Science in Nutrition from Texas State University and has spent the past 10 years specializing in maternal, infant, and child nutrition. Passionate about empowering mothers with reliable information and compassionate support, Jaclyn has honed her counseling skills through her extensive work in public health, helping families navigate breastfeeding challenges. Jaclyn has been instrumental in expanding the reach of the Oklahoma Breastfeeding Hotline, introducing innovative communication methods such as texting and telehealth to better serve families. Jaclyn is committed to advancing research on the benefits of breastfeeding and is actively involved in helping Oklahoma hospitals achieve Baby-Friendly Designation.

Sara McManus, MS

Financial and Administrative Manager at the Oklahoma Breastfeeding Resource Center (OBRC)

Sara began working for the Oklahoma Breastfeeding Resource Center (OBRC) in March of 2018. She started as a Staff Assistant where she supported OBRC staff as they managed multiple OBRC programs including the Becoming Baby-Friendly in OK program, the OK Breastfeeding Hotline and the Breastfeeding Education and Training initiative. She quickly grew to love OBRC’s mission and transformed into a breastfeeding and maternal/child health advocate. In her newest role as Sr. Program Coordinator, she continues her supportive role of all OBRC programs in addition to management of OBRC’s various contracts and grants that fund these initiatives.

Haley Richardson, BS

Education Program Coordinator at the Oklahoma Breastfeeding Resource Center (OBRC)

Bibliography

American Academy of Family Physicians. “Family Physicians Supporting Breastfeeding Position Statement.” 2022. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/breastfeeding-position-paper.html.

Baby-Friendly USA. The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative. Guidelines and Evaluation Criteria, 6th ed. 2021.

Baby-Friendly USA. “Babies Born in Baby-Friendly Hospitals as of October 1, 2024.” Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.babyfriendlyusa.org/.

Baby-Friendly USA. “Common Misunderstandings.” 2024. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.babyfriendlyusa.org/about/common-misunderstandings/.

Bartick, Melissa, and Arnold Reinhold. “The Burden of Suboptimal Breastfeeding in the United States: A Pediatric Cost Analysis.” Pediatrics 125, no. 5 (2010): e1048–e1056.

Bartick, Melissa, et al. “Cost Analysis of Maternal Disease Associated with Suboptimal Breastfeeding.” Obstetrics and Gynecology 122, no. 1 (2013): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e318297a047.

Bartick, Melissa, et al. “Suboptimal Breastfeeding in the United States: Maternal and Pediatric Health Outcomes and Costs.” Maternal and Child Nutrition 13, no. 1 (2017): e12366. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12366.

Burnham, Lori, et al. “Mississippi CHAMPS: Decreasing Racial Inequities in Breastfeeding.” Pediatrics 149, no. 2 (2022): e2020030502. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-030502.

Carothers, Cathy. Personal communication with author. September 27, 2024.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity: Data, Trends, and Maps.” 2020. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://nccd.cdc.gov/dnpao_dtm/rdPage.aspx?rdReport=DNPAO_DTM.ExploreByLocation&rdRequestForwarding=Form.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Breastfeeding Initiation Rates by County or County Equivalent in Oklahoma.” 2021. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/county/2018-2019/oklahoma.html.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity: Data, Trends, and Maps—Adult Obesity Status.” 2022. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://nccd.cdc.gov/dnpao_dtm/rdPage.aspx?rdReport=DNPAO_DTM.ExploreByTopic&islClass=OWS&islTopic=OWS1&islYear=20222022.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “2022 mPINC State Reports: Maternity Care Practices.” 2023. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/mpinc/state_reports.html.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Rates of Any and Exclusive Breastfeeding by State among Children Born in 2021.” 2024. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/nis_data/rates-any-exclusive-bf-state-2021.htm.

CHEER Equity. “Breastfeeding & Ten Steps Resources.” 2024. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://cheerequity.org/resources/breastfeeding-ten-steps-resources/.

DiGirolamo, Ann M., et al. “Effect of Maternity-Care Practices on Breastfeeding.” Pediatrics 122, Supplement 2 (2008): S43–S49.

Hakala, Minna, et al. “Implementation of Step 7 of the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) in Finland: Rooming-In According to Mothers and Maternity-Ward Staff.” European Journal of Midwifery 2 (2018): 9. https://doi.org/10.18332/ejm/93771.

Hudson, Jill A., et al. “Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative Is Associated with Lower Rates of Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia.” Breastfeeding Medicine 15, no. 3 (2020): 138–144. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2019.0220.

Li, Ruowei, et al. “Do Infants Fed from Bottles Lack Self-Regulation of Milk Intake Compared with Directly Breastfed Infants?” Pediatrics 125, no. 6 (2010): e1386–e1393. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-2549.

Li, Ruowei, et al. “Breastfeeding and Post-Perinatal Infant Deaths in the United States: A National Prospective Cohort Analysis.” The Lancet Regional Health – Americas 5 (2022): 100094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2021.100094.

March of Dimes. “Nowhere to Go: Maternity Care Deserts Across the US, 2024.” Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.marchofdimes.org/sites/default/files/2024-09/2024_MoD_MCD_Report.pdf.

Meek, Joan Y., Lori Noble, and AAP Section on Breastfeeding. “Policy Statement: Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk.” Pediatrics 150, no. 1 (2022): e2022057988. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2022-057988.

Merewood, Anne, et al. “Addressing Racial Inequities in Breastfeeding in the Southern United States.” Pediatrics 143, no. 2 (2019): e20181897.

Munn, Anne C., et al. “The Impact in the United States of the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative on Early Infant Health and Breastfeeding Outcomes.” Breastfeeding Medicine 11, no. 5 (2016): 222–230. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2015.0135.

Oklahoma Breastfeeding Resource Center. “Oklahoma WIC Infant Feeding Practices Survey.” Data presented at Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine Annual Conference, November 2023, Chicago, IL.

Oklahoma Breastfeeding Resource Center. “Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative.” 2024. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://obrc.ouhsc.edu/Baby-Friendly-Hospitals.

Oklahoma Breastfeeding Resource Center. “Lactation Care Deserts Map.” 2024.

Oklahoma State Department of Health. “Diabetes Dashboard.” 2024. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://diabetes.oklahoma.gov.

Oklahoma State Department of Health. “Oklahoma Obesity Prevalence, 2021.” Created August 31, 2023.

World Health Organization. “Protecting, Promoting, and Supporting Breastfeeding in Facilities Providing Maternity and Newborn Services: The Revised Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative 2018.” Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2018. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/272943.

Share this page:

More from Metrilineal

Scolded at the vasectomy pre-op: Family planning is a heavily gendered responsibility, and that doesn’t make sense

Scolded at the vasectomy pre-op Family planning is a heavily gendered responsibility, Read More

Government Mandated Parental Leave in Oklahoma: Addressing Structural Racism

Government Mandated Parental Leave in Oklahoma Addressing Structural Racism Abstract In 2023, Read More

Dispelling Myths about the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative

Dispelling Myths about the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative Abstract The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative Read More