Government Mandated Parental Leave in Oklahoma

Addressing Structural Racism

- Issue brief, Journal article

Catherine Harris, BSN, RN, CLC

PhD student, Fran and Earl Ziegler College of Nursing - University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center

Jennifer L. Heck, PhD, RNC-NIC, CNE, PMH-C

Associate Professor, Fran and Earl Ziegler College of Nursing - University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center

Abstract

In 2023, Oklahoma ranked 47th in America’s Health Rankings, dropping four spots—the largest decline of any state.

Nonclinical factors, including social, structural, and political determinants of health, shape outcomes. Structural racism, which drives race-based discrimination, limits access to paid parental leave in Oklahoma, worsening racial/ethnic birth inequalities. African American and Indigenous women—over half a million people—are disproportionately affected, facing poorer care, less prenatal/postpartum support, and higher maternal morbidity. As of 2020, they are twice as likely to die from maternal causes as non-Hispanic white women.

Without paid parental leave, the stressors associated with pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period are amplified, especially for marginalized communities. Early childhood investments at a societal and structural level, such as in policies that promote social welfare and eliminate structural racism, can positively impact children for a lifetime.

Oklahoma ranked 47th in the nation on America’s Health Rankings 2023 (Table 1),1International Labor Organization, “Care at Work.” representing the largest decline of any state’s health since the previous year (dropped four spots).

| Measure | 2023 value | 2023 rank |

|---|---|---|

| Social and Economic Factors | -0.639 | 44 |

| Physical Environment | -0.340 | 49 |

| Clinical Care | -1.109 | 48 |

| Behaviors | -1.040 | 47 |

| Health Outcomes | -0.435 | 41 |

| Overall | -0.709 | 47 |

As their names imply, social, structural, and political determinants of health (e.g., access to quality housing, racism/discrimination, accessible and affordable childcare) influence health outcomes.2Golembiewski et al., “Combining Nonclinical Determinants of Health,” 5. Specifically, structural racism (i.e., conditions that lead to racism/discrimination),3National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities, “Structural Racism and Discrimination.” adversely affects the health of historically marginalized groups. For example, housing policies like redlining create concentrated areas of poverty,4Richardson et al, “Redlining and Neighborhood Health.” prevent individuals from accessing higher education,5ACLU of Oklahoma, “Why Access to Education.” and create disproportionate imprisonment.6Brown, “Help End Disparities.” Early childhood investments at the societal and structural levels, such as social welfare policies, can positively impact children for a lifetime.7McGovern et al., “Relative Contribution.” Guaranteed access to parental leave is a crucial step in advocating for children and their future wellbeing whilst promoting the breakdown of barriers and elimination of disparities resulting from structural racism.

Inaccessible paid parental leave in Oklahoma’s public and private sectors heightens racial and ethnic inequalities, most notably at birth8Goodman et al., “Racial/Ethnic Inequalities,” 1. for African American and Indigenous people,9Putnam, “New Report Spotlights Imbalances.” who make up 17% of Oklahoma’s population.10County Health Rankings and Roadmaps, “Oklahoma.” Structural racism has been identified as a root cause of many maternal health disparities,11Riggan et al., “Addressing Allostatic Load.” resulting in poorer quality of overall care12Howell et al., “Black-White Differences,” 1. and less likelihood of prenatal and postpartum care.13Attansio and Kozhimannil, “Health Care Engagement.” These groups face more severe maternal morbidity such as shock and hysterectomy14CDC, “Identifying Severe Maternal Morbidity.” and life-threatening complications such as pre-eclampsia and postpartum hemorrhage,15Attansio and Kozhimannil, “Health Care Engagement.” some of which result in fetal or neonatal death.16Mengistu et al., “Impact of Severe Maternal Morbidity,” 3. For example, Oklahoma African American and Indigenous women are twice as likely to experience maternal death compared to non-Hispanic, white women.17Peterson et al., “Racial/Ethnic Disparities.” Stress after childbirth is amplified without comprehensive paid parental leave, especially for those with fewer resources and increased social needs (e.g., low income, less education, unemployment18Kreuter et al., “Addressing Social Needs,” 333.) due to structural racism.19Nomaguchi and Milkie, “Parenthood and Well-Being,”198-215.,20Kalil and Ryan, “Parenting Practices, Socioeconomic Gaps in Childhood Outcomes,” 29-50.

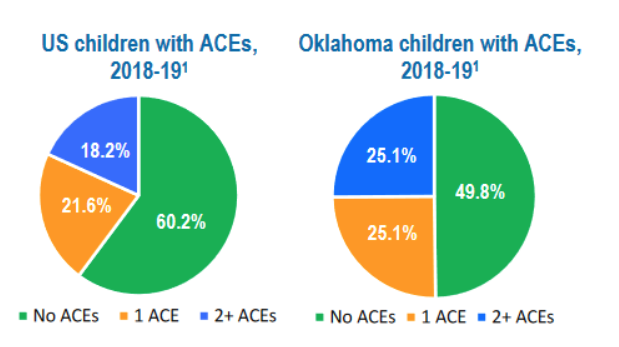

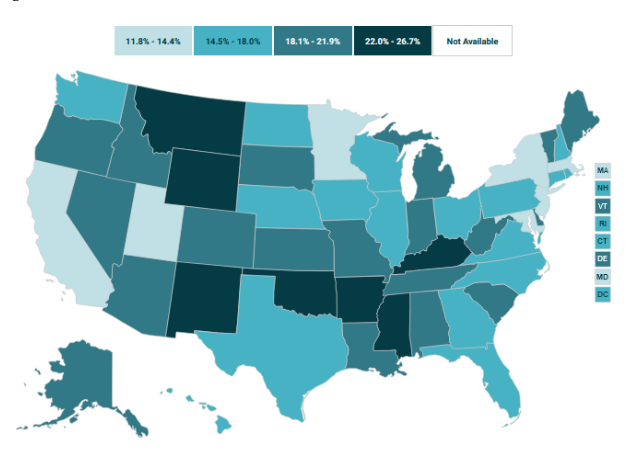

Because the U.S. does not regulate parental leave, the cycle of stress affects later generations, often for those experiencing the worst outcomes. Differential exposure, or the social variation in disease distribution and exposure to risk factors,21Lynch, “Uncovering the Mechanisms,” 1. is a foundational way that gender, race, ethnicity, and social class inequalities in health are produced.22Thoits, “Stress and Health,” 1. The cumulative damage caused by chronic stress and its potentially permanent effects can start as early as infancy.23“Home Page,” The Heckman Equation. Compared to the U.S. (18%),24County Health Rankings and Roadmaps, “Oklahoma.” 25% of Oklahoma children experience two or more adverse childhood experiences (ACEs; Figures 1 and 2),25SHADAC Analysis, “Percent of Children with Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs).” and 17% experience three or more ACEs, causing physical and mental health problems in adulthood.26Hughes et al., “The Effect of Multiple Adverse Childhood Experiences on Health,” 356.

Figure 1: U.S. and Oklahoma ACEs

Source: “Oklahoma Fact Sheet 2021,” Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative (CAHMI), Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Figure 2: Percent of children with 2+ ACEs 2021-2022

Source: SHADAC analysis of the National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH), State Health Compare, SHADAC, University of Minnesota.

Early life exposure to stress can affect children’s abilities to develop self-control skills and for making choices between immediate and delayed rewards,27Brocas, “Development of Time.” which are major determinants of risky health behaviors.28Thoits, “Stress and Health,” 1. Paid parental leave offers protection for parents and affects the child’s life trajectory, especially in those with increased social needs. Maternal, infant/child, family, and even societal outcomes may improve with universal paid parental leave.

Historical influences of parental leave

Since 1919, the International Labor Organization has recognized maternity leave as a universal human and labor right, with recommended baseline requirements.29Arneson, “Why Doesn’t the US Have Mandated Paid Maternity Leave?”,30International Labor Organization, “Care at Work.” The U.S. is one of only seven countries worldwide without federal, paid parental leave.31Watson, “Countries With Paid Maternity Leave.” Yet, Europe prioritizes it. After World War II, Europe sought to repopulate, hoping a strong workforce would rebuild the economy.32Peterson et al., “Racial/Ethnic Disparities.” They aimed to avoid further fascist tendencies or the social philosophy of ‘each man for himself,’ with political support for a welfare state that would create social and economic stability to support democracy.33Siegel, “Peace On Our Terms.” Therefore, paid parental leave was established.

Conversely, from its inception the U.S. favored individualism and self-determination,34Peterson et al., “Racial/Ethnic Disparities.” strongly opposing socialist tendencies, making social welfare policies with universal benefit difficult to achieve. Paid parental leave was an entitlement, allowing new parents to take advantage of the government.35Stephen-Miller, “How President Biden’s Paid FMLA Proposal Would Work.” Many believed a mandate would encourage the ‘wrong’ families to reproduce, reflecting structural racism targeting African American and immigrant people.36Brocas, “Development of Time.” Thus, private businesses are largely left to determine parental leave for employees, leaving nearly three in four Americans without.37U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Leave benefits by average wage category, private industry workers,” September 2022. People from historically marginalized groups often hold lower-paying, service and agricultural jobs, meaning they are disproportionately denied access to employer-provided parental leave.38Brocas, “Development of Time.”

Cutting through the red tape

Arguments against U.S.-mandated, paid parental leave stem from disagreements about policy structure and funding.39Arneson, “Why Doesn’t the US Have Mandated Paid Maternity Leave?” Many Americans resist government interference in such policies, worrying that businesses would shoulder the financial burden of any national mandate.40Peterson et al., “Racial/Ethnic Disparities.” In April 2024, President Biden proposed a medical and family leave policy with 12 weeks of paid time off, funded by a combination of raising income tax on the wealthiest one percent and increasing capital gains and dividend tax rates.41Brocas, “Development of Time.” In a recent advisory, the U.S. Surgeon General challenged policymakers to establish a national paid family and medical leave program to ensure all workers have paid sick time.42Office of the Surgeon General, “Parental Mental Health.” Several states have already enacted policies that help businesses retain employees beyond childbirth.43Peterson et al., “Racial/Ethnic Disparities.” When the Covid-19 pandemic forced over 3,000,000 women to leave the workforce, the economic benefit of social support for families through paid parental leave became clear.44Cerullo, “Nearly 3 million,” CBS News.

Ralph Waldo Emerson once referred to America as ‘another name for opportunity’ but was critical of its focus on society’s progress rather than individual development.45Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Self-Reliance.” Nearly 150 years later, biased systems remain, with only 8% of individuals in the bottom quarter of wage-earners receiving paid parental leave.46Arneson, “Why Doesn’t the US Have Mandated Paid Maternity Leave?” As Oklahoma is designated as rural47Rural Health Information Hub, “Rural Maternal Health Overview.” (with most counties having maternal care desserts48Oklahoma Policy Institute, “2023 Census Data.”) and has more disproportionately disadvantaged populations such as U3 (i.e., underrepresented, underserved, underreported),49National Institute of Health, “U3 Interdisciplinary Research.” obstacles to overcome these disparities are vast. Ultimately, inaccessible paid parental leave sets the precedent that our children are not a priority. As the U.S. Surgeon General advises, guaranteed access to paid parental leave could significantly improve many Oklahoma health outcomes. We don’t have much further to fall.

About the authors

Catherine Harris, BSN, RN, CLC*

PhD student, Fran and Earl Ziegler College of Nursing - University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center

Catherine is a current student in the PhD in Nursing Education program at the University of Oklahoma. In addition, she works part time in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at a local hospital, working bedside, advocating deliveries and stabilizing high-risk neonates. She is also a certified lactation counselor, where she helps mothers learn to breastfeed.

*corresponding author

Jennifer L. Heck, PhD, RNC-NIC, CNE, PMH-C

Associate Professor, Fran and Earl Ziegler College of Nursing at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center

Dr. Jennifer Heck is faculty with the University of Oklahoma Fran and Earl Ziegler College of Nursing. She is an associate professor in the Child and Family Health Sciences Department and a maternal newborn health nurse, advocate, and researcher.

References

“2023 Census data: Oklahoma ranks sixth poorest state.” Oklahoma Policy Institute, September 2024. https://okpolicy.org/2023-census-data-oklahoma-ranks-as-sixth-poorest-state/.

Arneson, Krystin. “Why Doesn’t the US Have Mandated Paid Maternity Leave?” BBC News. February 25, 2022. https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20210624-why-doesnt-the-us-have-mandated-paid-maternity-leave.

Attanasio, Laura, and Katy B. Kozhimannil. “Health Care Engagement and Follow-up after Perceived Discrimination in Maternity Care.” Medical Care 55, no. 9 (September 2017): 830–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0000000000000773.

Brocas, Isabelle. “The Development of Time Preferences in Children.” Psychology Today, February 26, 2024. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/biology-development-and-behavior/202402/the-development-of-time-preferences-in-children.

Brown, Sabine. “Help End Disparities in Oklahoma’s Criminal Justice System.” Together Oklahoma, March 11, 2019. https://togetherok.okpolicy.org/help-end-disparities-in-oklahomas-criminal-justice-system/.

“Care at Work: Investing in Care Leave and Services for a More Gender Equal World of Work.” International Labour Organization, July 5, 2024. https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/care-economy/WCMS_838653/lang–en/index.htm.

“Compare Oklahoma and United States.” America’s Health Rankings, 2024. https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/measures/Overall/OK/compare.

Cerullo, Megan.“Nearly 3 Million U.S. Women Have Dropped out of the Labor Force in the Past Year.” CBS News, February 5, 2021. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/covid-crisis-3-million-women-labor-force/.

Golembiewski, Elizabeth, Katie S. Allen, Amber M. Blackmon, Rachel J. Hinrichs, and Joshua R. Vest. “Combining Nonclinical Determinants of Health and Clinical Data for Research and Evaluation: Rapid Review.” JMIR Public Health and Surveillance 5, no. 4 (October 7, 2019). https://doi.org/10.2196/12846.

Goodman, Julia M., Connor Williams, and William H. Dow. “Racial/Ethnic Inequities in Paid Parental Leave Access.” Health Equity 5, no. 1 (October 1, 2021): 738–49. https://doi.org/10.1089/heq.2021.0001.

“Home Page.” The Heckman Equation. April 20, 2020. https://heckmanequation.org/.

Howell, Elizabeth A., Natalia Egorova, Amy Balbierz, Jennifer Zeitlin, and Paul L. Hebert. “Black-White Differences in Severe Maternal Morbidity and Site of Care.” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 214, no. 1 (January 2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2015.08.019.

Hughes, Karen, Mark A Bellis, Katherine A Hardcastle, Dinesh Sethi, Alexander Butchart, Christopher Mikton, Lisa Jones, and Michael P. Dunne. “The Effect of Multiple Adverse Childhood Experiences on Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” The Lancet Public Health 2, no. 8 (August 2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-2667(17)30118-4.

“Identifying Severe Maternal Morbidity (SMM).” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed November 16, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/maternal-infant-health/php/severe-maternal-morbidity/icd.html.

Kalil, Ariel, and Rebecca Ryan. “Parenting Practices and Socioeconomic Gaps in Childhood Outcomes.” The Future of Children 30, no. 2020 (2020): 29–54. https://doi.org/10.1353/foc.2020.0004.

Kreuter, Matthew W., Tess Thompson, Amy McQueen, and Rachel Garg. “Addressing Social Needs in Health Care Settings: Evidence, Challenges, and Opportunities for Public Health.” Annual Review of Public Health 42, no. 1 (April 1, 2021): 329–44. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-102204.

Lynch, Elizabeth B. “Uncovering the Mechanisms Underlying the Social Patterning of Diabetes.” EClinicalMedicine 19 (February 2020): 100273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100273.

Mengistu, Tesfaye S., Jessica M. Turner, Christopher Flatley, Jane Fox, and Sailesh Kumar. “The Impact of Severe Maternal Morbidity on Perinatal Outcomes in High Income Countries: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Clinical Medicine 9, no. 7 (June 29, 2020): 2035. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9072035.

McGovern, Laura, George Miller, and Paul Hughes-Cromwick. “The Relative Contribution of Multiple Determinants to Health Outcomes.” Healthy People 2020, August 2014. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/about/foundation-health-measures/Determinants-of-Health.

“Native American Population by State.” World Population Review. Accessed September 19, 2024. https://worldpopulationreview.com/state-rankings/native-american-population.

Nomaguchi, Kei, and Melissa A. Milkie. “Parenthood and Well‐being: A Decade in Review.” Journal of Marriage and Family 82, no. 1 (January 5, 2020): 198–223. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12646.

Office of the Surgeon General. “Parental Mental Health & Well-Being.” HHS.gov, August 28, 2024. https://www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/priorities/parents/index.html.

“Oklahoma.” County Health Rankings & Roadmaps, 2024. https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/health-data/oklahoma?year=2024.

“Oklahoma Fact Sheet 2021: Strong Roots Grow a Strong Nation.” Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative (CAHMI). Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. https://www.cahmi.org/docs/default-source/resources/2021-aces-fact-sheets/cahmi-state-fact-sheet—ok.pdf?sfvrsn=e088a677_6.

Parker, Judy Goforth. “Health Policy Newsletter,” 1(4). 2021. The Chickasaw Nation.

“Percent of Children with Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs).” SHADAC analysis of the National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH). Accessed November 16, 2024. https://statehealthcompare.shadac.org/map/243/percent-of-children-with-adverse-childhood-experiences-aces-by-total#173/77/279.

Petersen, Emily E., Nicole L. Davis, David Goodman, Shanna Cox, Carla Syverson, Kristi Seed, Carrie Shapiro-Mendoza, William M. Callaghan, and Wanda Barfield. “Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Pregnancy-Related Deaths — United States, 2007–2016.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 68, no. 35 (September 6, 2019): 762–65. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6835a3.

Putnam, Carly. “New Report Spotlights Imbalances among Child Well-Being for Oklahoma’s Children of Color.” Oklahoma Policy Institute, January 2024. https://okpolicy.org/new-report-spotlights-imbalances-among-child-well-being-for-oklahomas-children-of-color/.

Richardson, Jason, Bruce C Mitchell, Helen C. S. Meier, Emily Lynch, and Jad Edlebi. “Redlining and Neighborhood Health.” National Community Reinvestment Coalition, June 28, 2023. https://ncrc.org/holc-health/.

Riggan, Kirsten A., Anna Gilbert, and Megan A. Allyse. “Acknowledging and Addressing Allostatic Load in Pregnancy Care.” Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 8, no. 1 (May 7, 2020): 69–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00757-z.

“Rural Maternal Health.” Rural Health Information Hub. Accessed February 7, 2024. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/maternal-health.

“Emerson’s Self-Reliance: Unleash Your Inner Strength and Embrace Independence.” Ralph Waldo Emerson, February 27, 2024. https://emersoncentral.com/texts/essays-first-series/self-reliance/.

Siegel, Mona L. Peace on our terms: The Global Battle for Women’s rights after the First World War. New York: Columbia University Press, 2021.

Miller, Stephen. “How President Biden’s Paid FMLA Proposal Would Work.” Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM), May 4, 2021. https://www.shrm.org/topics-tools/news/benefits-compensation/how-president-bidens-paid-fmla-proposal-work.

“Structural Racism and Discrimination.” National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities, September 2024. https://nimhd.nih.gov/resources/understanding-health-disparities/srd.html.

Thoits, Peggy A. “Stress and Health: Major Findings and Policy Implications.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 51, no. 1 (March 2010). https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510383499.

Watson, Janelle. “Countries with Paid Maternity Leave: How the US Compares.” Justworks, December 21, 2023. https://www.justworks.com/blog/countries-with-paid-maternity-leave.

“U3 Interdisciplinary Research.” National Institutes of Health. Accessed November 16, 2024. https://orwh.od.nih.gov/womens-health-research/interdisciplinary-research/u3-interdisciplinary-research.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Table 7. Leave benefits by average wage category, private industry workers, March 2022,” in “National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in the United States, March 2022,” September 2022. Excel file (“private-average-wage-category-2022″). https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2022/home.htm.

“Why Access to Education Is Key to Systemic Equality.” ACLU of Oklahoma, September 7, 2023. https://www.acluok.org/en/news/why-access-education-key-systemic-equality.

Share this page:

More from Metrilineal

Scolded at the vasectomy pre-op: Family planning is a heavily gendered responsibility, and that doesn’t make sense

Scolded at the vasectomy pre-op Family planning is a heavily gendered responsibility, Read More

Government Mandated Parental Leave in Oklahoma: Addressing Structural Racism

Government Mandated Parental Leave in Oklahoma Addressing Structural Racism Abstract In 2023, Read More

Dispelling Myths about the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative

Dispelling Myths about the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative Abstract The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative Read More