Naming and Framing Obstetric Racism to Enable Change

- Op-ed

Eliza Washington-Harris, RMSc

Data & Policy Research Coordinator, Metriarch

A mix of systemic and interpersonal racism places Black people in a specifically vulnerable position within the American medical space. For Black people who give birth in the US this is especially true, partially due to obstetric racism.

Obstetric racism refers to acts of racism that occur within the context of reproductive health services. Acts of obstetric racism strip birthing people of their autonomy, cause physical or emotional pain, and can ultimately put them at risk of complications or death.

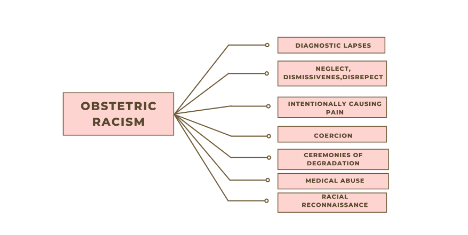

There are seven elements of obstetric racism: lapsed diagnosis; neglect, dismissiveness, or disrespect; deliberately causing pain; coercion; ceremonies of degradation; medical abuse; and racial reconnaissance.

Naming obstetric racism when it occurs enables us to acknowledge the impact that racism can have on Black people’s reproductive care. The language that we use to describe Black people’s birthing experiences matters.

For Black people giving birth in the US, this naming provides a pathway for legitimizing the pain felt by those who have been dismissed, disrespected, or degraded while receiving reproductive healthcare. It enables them to put these encounters into perspective and to understand that they are not alone. For some, naming their experiences offers a voice within a larger narrative.

Framing obstetric racism means that we situate these instances within a larger picture of systemic racism in the US. This allows us to pull together a larger picture from separate instances of obstetric racism and violence. When Black people experience neglect, missed diagnoses, or are treated with the assumption that they feel less pain than their peers while giving birth, it’s important to understand that these are not isolated events. Their frequency is indicative of larger sociocultural inequities. These inequities lead Black people to die at three times the rate of white peers during childbirth. Black people also experience higher rates of adverse birth outcomes, including infant mortality.

Language which separates instances of medical neglect or abuse from their historic and sociocultural context shifts our focus to the interpersonal or individual impact of these adverse birth experiences rather than the structural factors that underpin them. By naming obstetric racism and framing it within a larger context, we are able to see a larger pattern of mistreatment that goes beyond individual victims. This allows us to make progress towards meaningful change through action planning, which is cognizant of the flawed system and does not place individual blame. We are not fighting doctors, we’re fighting a larger system which is historically, socio-culturally, and geographically situated.

The myth that Black women do not experience pain or experience it to a lesser degree than white counterparts has existed since transatlantic slave trade. This myth had a heavy influence on modern obstetrics and gynecology. The origins of these practices are rooted in the inhumane and exploitative treatment of enslaved black women.

The “father of modern gynecology,” Dr. James Marion Sims, was white slave-owner who performed unanesthetized surgery on enslaved women who were unable to consent and later treated anaesthetized white patients once he had perfected his techniques. As these acts were taking place, existing knowledge systems and black midwifery were also being forced out of discourses on women’s health.

This exploitation continued into the 20th century in the forms of sterilization abuse, obstetric racism, and contraceptive experimentation. Meaningful and sustainable change will depend on our ability to understand these historic and systemic factors and counteract them. This means empowering physicians with knowledge about structural racism, implicit bias, and intercultural competency. Moreover, we can empower Black people to know what obstetric racism looks like and who they can turn to for support.

Increasing the visibility and availability of doulas to people of colour could provide them with advocates in the birthing space. Doula work has been shown to enable agency, personal security, and knowledge among other factors, thus facilitating a good birthing experience.

We must also empower people giving birth with the knowledge necessary to make informed decisions about their care. Oklahoma has taken strides towards this empowerment through the TeamBirth framework which is predicated on the idea that birthing people have a voice that needs to be heard in the birthing room alongside the voices of physicians and other support people.

Patient self-advocacy helps patients themselves in the moment, but it also provides an avenue for educating physicians which can have long term effects. Informing physicians about implicit and systemic bias reduces the likelihood that someone will experience obstetric racism during perinatal care or delivery. Thus, educating and empowering anyone in the room to make informed and unbiased decisions benefits the entire system

Share this page:

You might also like

Patient and Provider Perceptions of Opill®

Patient and Provider Perceptions of Opill® *corresponding author As the first FDA-approved Read More

Scolded at the vasectomy pre-op: Family planning is a heavily gendered responsibility, and that doesn’t make sense

Scolded at the vasectomy pre-op Family planning is a heavily gendered responsibility, Read More

Government Mandated Parental Leave in Oklahoma: Addressing Structural Racism

Government Mandated Parental Leave in Oklahoma Addressing Structural Racism Abstract In 2023, Read More